Why I Write

It’s taken many years for me to say “I am a writer” with confidence. It’s a bold statement. People respond with “what have you published” and if you haven’t published much it can be a sheepish response. But after 20 plus years as a contributing columnist at the Hamilton Spectator and several publications elsewhere, I think I can safely lay claim to having at least one foot in the occupation.

I’m not a writer because I get paid to write. That’s fantastic, but it could stop at anytime and I would still be a writer. Sadly a much poorer one. I’m a writer because I need to write. It’s how I make sense of the world, by working it out and writing it down. It’s how I participate in democracy by weighing the issues through a rational process before I vote on them. And I write because I love words and how they sound and work together to create meaning.

Online publishing, like this account at Substack or my fiction account at Medium, allows writers to set up shop directly with readers, bypassing the cultural and information gatekeepers who have their own agenda, and rightly so, each publication has a voice and values it wants to advance. For the dissenting voices, or the voices against the grain, independent voices or new voices looking for readers, finding those readers by taking their work directly to their audience isn’t as impossible as it once was. But it’s not easy either.

People consume information very differently today. When I was young, we’d watch the news as a family, discuss topics in the daily paper around dinner time. The radio brought us news on the hour. Those news shows are still there, but viewing habits have changed dramatically. Where once it was communally consumed, the family sitting around the TV, it’s now individual, hand-held and for our eyes only unless we share. Where once a handful of media companies controlled the message, now it’s like the wild, wild, west and anyone can say anything to anybody. But equal access is not guaranteed. Meta has restricted the sharing of news for its Canadian users because of government policies designed to return lost ad revenue to Canadian content creators.

The 21st century digital information revolution is reminiscent of the explosion in knowledge precipitated by the printing press. Hand bills and pamphlets appeared on the literary scene, challenging governments and policies, exposing corruption, advocating for change. Literacy rates increased. Controlling the free press, and the population, has been a challenge ever since. The corporatization of media as it progressed over the last half century has seen increasing concentration of of media ownership in corporate investment portfolios. The principles informing the fourth estate are compromised by those that inform capitalism. Capitalism seems to be winning as media companies cut staff and reduce news coverage, dumbing down the population in the process.

The online platform is the new printing press and the resulting explosion in content and knowledge creation has brought us to a new place in human consciousness. But it’s not without its perils and pitfalls. Trust has become an issue.

We are divided within our own communities, almost everywhere. Our political and social discourse has breached any boundaries of respect or civility it once had. Our interpersonal communication is suffering from digital interference; we are losing the intangibles of in-person communication, the verbal and visual cues that inform and enhance meaning. We are becoming bits and bytes in our communications, the expression of emotion reduced to emojis while three-word taglines dominate political discourse.

Now that AI has wormed its way into the creative arena, trust is having a battle on its hands. Anyone with a passing familiarity with Photoshop knows better than to believe images so easily manipulated, demonstrated earlier this year when the Princess of Wales was caught out posting doctored images. Her excuse, abbreviated, was: everyone’s doing it.

My pledge to you is that I will never use AI (aside from spell check) when I write. It’s all me. If I bring in ideas or words not my own, I will credit them. I will ensure that the facts are true before I repeat them. I will not spread disinformation and misinformation and will respond with facts.

I declare my bias is towards a compassionate humanity that meets people where they are, and is often in support of left policies. I believe in the lessons from the past, that climate change is real, and that children are our future.

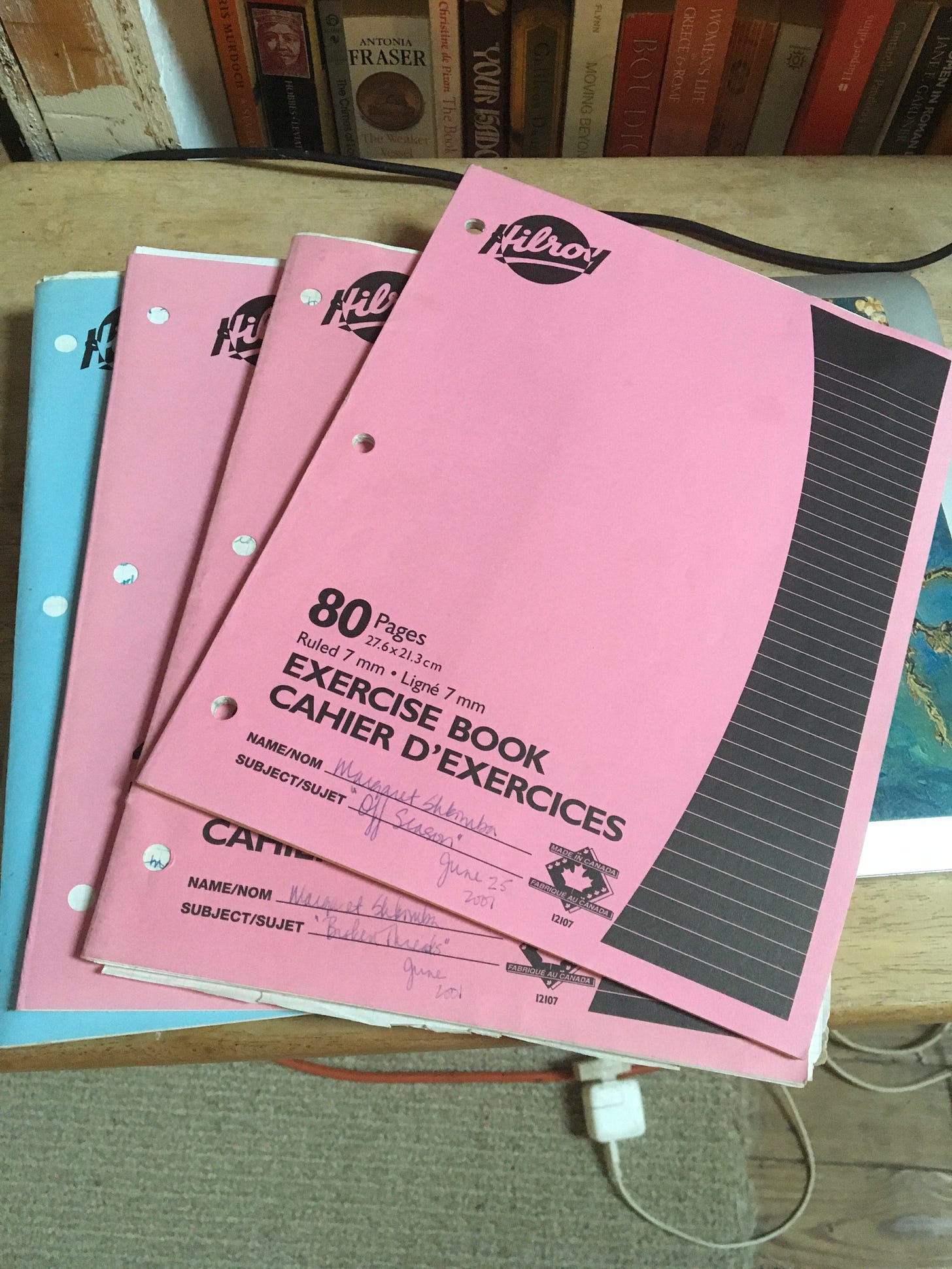

Writing can be a self-indulgent past time. But I do my best to stay grounded in the reality that this is a responsibility, that it has to mean something. It’s a heavy responsibility, holding a person’s attention, asking them to follow along some pretty trippy paths to a conclusion with which they might not agree. Best to have something to say, in an engaging voice, and present proof to back it up. Except for fiction. More fun there, but less output. At this point.

Importantly, I need to write as a spectator and witness to our times. And they are exciting times. Much of what we know of the past has come to us through the words of writers, scribes, recorders of events. A picture tells a thousand words, but it tells only the surface story. To know more, you have to dig deeper into what was written about events by the people who were there, by the witnesses. In some small way, it’s my contribution to the historical record. A debt I owe to the education I received and the world in which I live.

However, I do worry about the longevity of the electronic medium over hard copy in the face of apocalyptic destruction. Even the survival of the hard copy edition could be a miracle. We’re not pressing a stylus into clay tablets anymore and paper burns. And when the power goes out…. But that’s a story for another time.